Once upon a time, Bihar was one of the richest regions of India. The Kosi River and its tributaries, rich with sparkling silt, created verdant farmland. As a naturally meandering river, the Kosi had room to roam and spread its abundance over wide swaths of land. Monsoon season was manageable because the river’s shape shifted to accommodate the overflowing water supply.

The blessings of the Kosi have taken a dark turn. Climate change and attempts to control the river by building ill-advised embankments have conspired to make the yearly monsoon intensify into devastating floods, a phenomenon now referred to by locals as “the curse of the Kosi.” Unable to get their feet back under them during a constant barrage, communities in Bihar are now among the poorest in India. The Kosi River is known nowadays as “the sorrow of Bihar.”

Many small-scale farmers live in the known flood zone of the Kosi. A few generations past, these stomping grounds were safer than they are now. Their grandparents and great-grandparents settled there, though it was technically illegal to live in the government-owned land. While India as a whole is moving past the caste system, in rural areas the traditional divides are still strong. As untouchables, those who moved into the flood zone did not have the money to buy land, and landowners were unwilling to rent land to members of the lowest caste.

Flooding of the Kosi is too severe to reasonably live on its banks, but these families have had few choices. The tide, however, may be turning. Women are rising up to break the limitations of class and traditional gender roles to seek better lives for themselves and future generations.

Sharada Devi, 48 years old and a mother of eight children, felt lost and alone in her home village of Tarwara in the state of Bihar. As a member of the lowest caste, she simply didn’t have options in her life, so she worked as a laborer in another, richer farmer’s field. Her husband, Gulma Sada, 53, had to leave her and her children to find work in the faraway town of Punjab. Sharada Devi was only earning 100 rupees a day, the equivalent of $1.50. Even with what her husband was able to earn in the city, there was not enough. The whole family only ate once a day.

“I had no clue at that time exactly what I should do,” Sharada Devi said. Two years ago, Heifer started a project in her area offering goats and training. When Heifer partners came to Tarwara and explained the project, Sharada Devi realized she had a chance to change things. She joined and focused her energy on raising goats.

While she had a couple of goats before, the gift of good quality goats and the all-important training on the care of their goats changed everything. Sharada Devi increased the size of her herd and the quality of the animals, building momentum. Today she earns around 15,000 rupees a month, or $224.46. This eclipsed what her husband was making in Punjab, so he was able to come home to his family and join in the new business. “He will stay,” said Sharada Devi.

Now the family eats breakfast, lunch and dinner, and the quality of food they eat is better than ever. Sharada Devi received the seeds and training necessary to grow a kitchen garden for the family, and now they eat vegetables almost every day. They can even afford meat about once a week. Beforehand, their one meal a day consisted mostly of rice or an Indian style of flatbread called chapatti. Sharada Devi’s favorite food now is fried okra spiced with turmeric, onion, garlic, green pepper, cardamom and a pinch of salt.

The family members aren’t the only ones getting three square meals a day. “Whenever I eat, I go to give the goats food,” Sharada Devi said. The training Sharada Devi received taught her how to grow her own fodder, best practices on how much to feed and water her goats, how to take care of their health and hygiene, and how to house them in a clean shed. She learned everything that makes for happy, healthy goats, which will ultimately be all the more profitable for her.

Now that her husband is back for good and has taken Heifer’s gender equity training, the goat business and their home life are both mutual endeavors. “When I am cooking, I ask him to feed and water the goats sometimes. If I have to buy something from the market, I ask him to go and buy it.” Before, Sharada Devi shouldered the full workload of the home in addition to her farming labors.

The new perspective is already being passed down to the next generation. Now, Sharada Devi said, “I am treating equally my daughters and sons. Before my focus was only on boys. [Now], if I buy a goat for my boy, I buy a goat for my daughter also. I send both my sons and daughters to school.”

The annual floods still threaten Sharada Devi’s newfound success. That’s why her training included disaster preparedness. The flood waters come up to Sharada Devi’s door almost every year. “[When it floods], I am not able to sleep at night,” she said. She has learned how to make temporary rafts from banana trees and how to construct high bamboo shelters for the family and their animals. They learned how to save food ahead of time so they can still eat when the farmland is flooded and it is too dangerous to leave their home. Most importantly, Sharada Devi said, “I learned how to protect myself and my family.”

Munni Devi and other women in her community weren’t so sure about joining the Heifer project in her home village of Bhathaili when they first heard about it. The lynchpin of the project is bringing women together in self-help groups, or community groups that work together to save money, make loans to each other and otherwise help each other make a living. Munni Devi and the women in her village mostly worked in isolation, sometimes forming groups of three or four friends. They wondered if the large group of 17 Heifer was proposing would be able to get along. Munni Devi already had so little, and being part of the project meant each woman invested money into the group regularly. “What if the people start fighting amongst themselves, and my money will go to waste?” she thought.

Munni Devi’s neighbor Priyanka Devi was enthusiastic about the idea, however, and she eventually sold it to Munni Devi and the other women in the group. After a few months, the women formed a deep trust and their fears disappeared.

Now the bond between the women in the self-help group is one of the most meaningful parts of the project for Munni Devi. Before, she said, they only saw each other at special occasions. But the group gave them a reason to come together. They work together, and through this common purpose they bonded.

Gender equity and facilitating supportive communities among women is a priority in Heifer projects worldwide. If you want to support the amazing women we work with, consider donating.

“Earlier, we were small groups of three or four. Now we are 17 women coming together. We have become a much stronger group,” Munni Devi said, sitting on her bed with four other group members gathered closely beside her. It is easy to see the affection between them as they sit closely on the bed, another friend showing up and hopping in with the rest every few minutes, greeted by hugs and laughter. Munni Devi says this is an example of the difference the project has made. “Before joining the group, we were not used to sitting together. She was involved with her activities, she was involved with her activities. Everyone was working alone.” Now, she says, if someone has work to do in their gardens or with their goats, the other group members come together to help each other. “Something that would take two hours before, we are able to manage it in one.”

With the extra time, Munni Devi and the others in her group hope to turn one of their passions into productive work. They see that in the future, the lack of land will eventually bottleneck their agricultural growth. So they have ambitions to take a skill they all know—sewing—and turn that into income, too. It also appeals to them because it is work they can do together. “Money is of course there,” Munni Devi said. “But besides the money, in things like this, we get to work together. We get to spend time together.”

If we find something good and we think we should do it, we just do it. We cannot be stopped.

Munni Devi

In rural India, women rarely have power to decide their own futures. When the women in Bhathaili first started the project, their husbands hesitated. “But very soon they began to see the return because of us,” Munni Devi said. “Because the women are taking part, it is beneficial for their household. It is saving them. So, they have become agreeable, and they are also taking part.”

Before this project, women said they could not speak up if they disagreed about a decision their husbands made. But now, if they are convinced that a decision is good, they convince their husbands. Priyanka Devi reports they now say to their husbands, “If I am logical, how can you say no?”

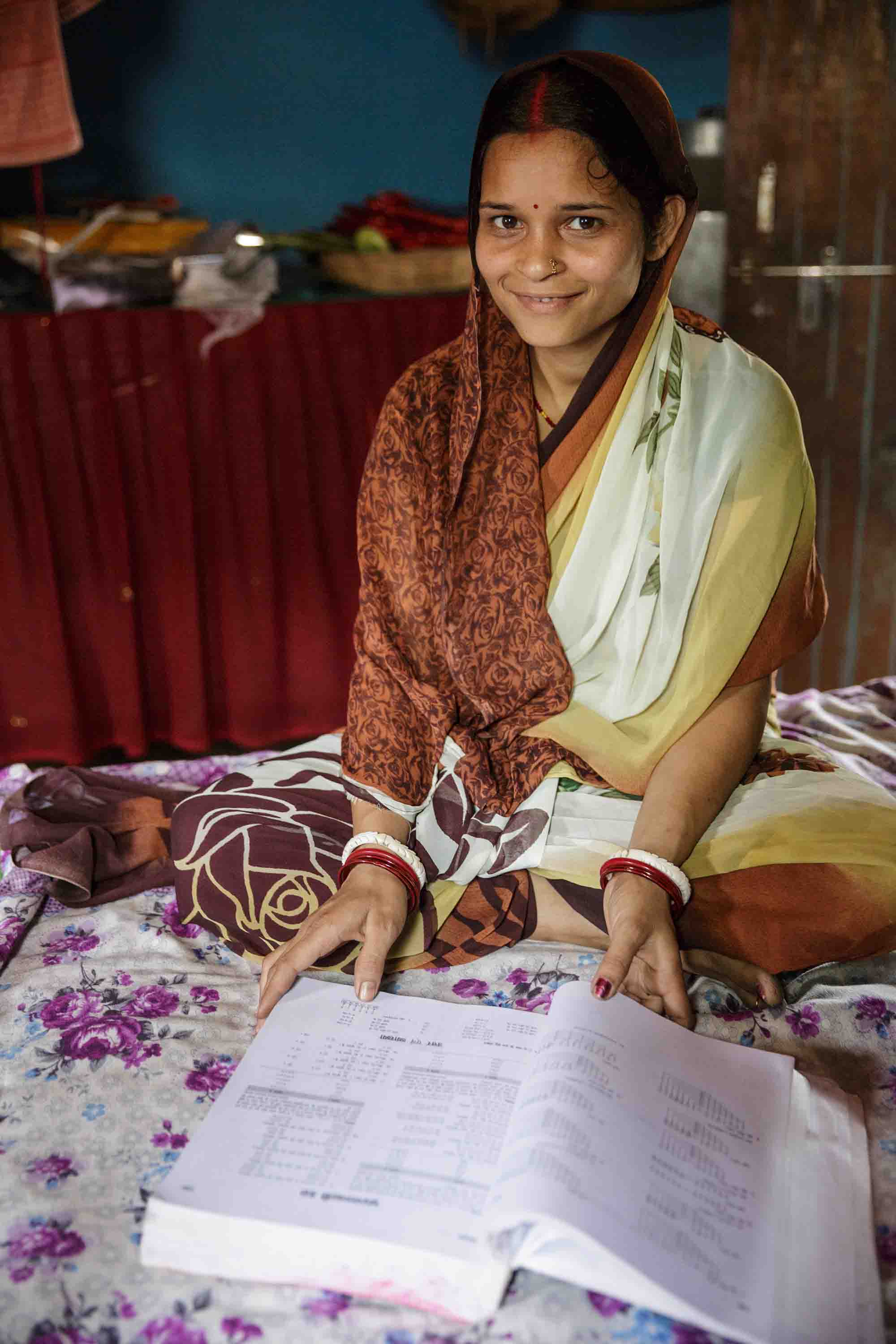

Munni Devi’s sons did not get a chance to study, but it’s a different story for her daughter, Preeti Kumar. Munni Devi proudly revealed that Preeti is literate in both written language and computer science. As part of the project, Heifer set up a literacy program to teach women in the self-help group who are not yet literate. Preeti Kumar is the appointed teacher in Bhathaili.

Before the project, Munni Devi and the women in her group were scared of change. Now, they have abandoned fear for confidence. “If we find something good and we think we should do it, we just do it,” said Munni Devi. “We cannot be stopped.”

Higher education is rare for men and nigh-on unheard of for women in the village of Begumpur. The general attitude was that if anyone got to go to school, it would be boys. Educating girls is pointless since they will just get married and go live with their husbands. If you educate a son, the thinking goes, he will support you.

But growing up, Puja Devi liked studying. She had only made it to 10th grade when she married Chandresh Kumar Das, but Puja Devi agreed to marry on the condition that he would allow her to continue her studies. It was an unusual proposal for their culture, but Puja Devi and Das did it anyway. Against all odds, she graduated college in 2017.

There was a time when she very nearly gave up. They were so poor, she said, there was not enough money to study and take care their home and family. “We were all very weak,” she said, due to lack of nutrition. When Heifer taught them how to raise goats and they started making money and eating well, she decided to restart her studies. She persisted until she graduated. “I’m very happy,” she said. “I was thrilled to not only graduate but graduate with good marks. Now I want to study more."

Psychology was Puja Devi’s favorite subject because “it explains why people do the things they do,” she said. But Puja Devi aspires to earn a more advanced degree in education and become a certified teacher. That way, she can teach full-time in school rather than the after-school Hindi and English classes she currently teaches. Puja Devi’s plan is to not let any child in the community go uneducated. She intends to go door to door and ask parents to send their children to school, boys and girls. If they say no, she said, she will convince them with her own story of how she got an education and how it changed her life. Puja believes that education can bring the community out of poverty. “This is the only way in which we can pull them out of their misery.”

Rashmi Nandan Kisku caused a stir in the remote village of Sauntha when she started pedaling around town on a bicycle. She was the first girl in town to ride a bike. Many in Sauntha disapproved and approached her mother, Lakshmi Kisku, to tell her so. But Lakshmi Kisku was resolute in her decision to give her daughter a bike. “I want her to ride a bicycle,” she said. “I think they should also think like that. Why should we be behind anyone?”

Lakshmi Kisku is a 30-year-old mother of three girls and founding director of a Heifer-supported produce company. The company is a coalition of small-scale women farmers who formed a for-profit company. Lakshmi Kisku is a forward-thinker and go-getter in Sauntha. She was inspired to get Rashmi a bicycle when her work took her to Delhi. The trip to the progressive capitol opened her eyes to the possibilities for women and girls. “More than the houses and the roads,” she said, “I saw people free. The sense of freedom even for girls. Girls on bikes!”

Lakshmi Kisku came back from Delhi with a new vision for women in her community. “I want to bring change out here,” she said. “Even if it is a little harder to achieve here, I want to see the change.”

Lakshmi Kisku has come a long way since 2010, when she was 22 and a member of a newly-formed Heifer project. She joined hoping to save money through a self-help group with other women. At the time she and her husband didn’t have any savings, or even a bank account. Like most people in Bihar, she and her husband were day laborers in other farmers’ fields, and they didn’t have enough food or medicine. Lakshmi Kisku and her husband had to choose between food and medicine, and the whole family stayed sick most of the time. Rashmi was malnourished, and even today she is small for her age.

“I was always troubled,” Lakshmi Kisku said, remembering that time.

The gift of two goats and some business training turned it all around. She realized that owning goats provides a sense of security as well as a form of income—goats are so easy to sell in her rural setting, they work like an ATM for her. Today she has 17 goats. Lakshmi and her fellow project members’ success led them to form the produce company. So far the company has sold rice, maize and goats.

Lakshmi Kisku has risen to a position of leadership she never imagined before. One of her trips to Delhi was to make a presentation about the company to a group of potential investors and buyers. Heifer India helped set up this Shark Tank-esque meeting, and Lakshmi Kisku rose to the occasion. Speaking out is a new paradigm for Lakshmi. “I was very scared and shy earlier,” she remembered. “But then we started doing Pass on the Gift events. And these events were often attended by people from banks and other [important] people.” Lakshmi Kisku got her start speaking publicly at these community events, so that by the time she went to Delhi for the big presentation she was a pro.

When Rashmi finished first in her class, Lakshmi Kisku threw her daughter a party. A lot of people came, including members of the upper caste. Before the Heifer project, Lakshmi Kisku would not even come out of her house if someone from a high caste was walking by. In many parts of India, an upper caste woman would not let a lower caste person even enter their house or kitchen. But Lakshmi Kisku found herself cooking with an upper caste friend. “I feel very proud of what I have achieved,” she said. “Now I have achieved the level where I am entering the house and sitting equally with upper caste people.”

Lakshmi Kiksu is most proud of the impression she has made on her daughters. Rashmi told her one day, “You are not a simple person. You have been to the place where the prime minister goes and speaks. You went and spoke there. You are not ordinary. You are a special person.”

Lakshmi Kisku’s leadership skills were on display during the especially destructive floods in the fall of 2017. Lakshmi Kisku and the other directors pooled cash and raised money so they could donate relief kits 600 families. “We did the flood relief because we realized our company should not do business only for profit,” Lakshmi Kisku said. “If we can do some work for humanity, and we can raise funds, we will also engage in that activity. And we should. Because we are all at the same level. No one is going to come [from] outside. We are here.”