How Does Hunger Affect Learning?

By Alyssa Cogan | October 28, 2021

The first 1,000 days of a child’s life — from conception to a child’s second birthday — are a critical window for healthy growth. During this period, children experience rapid brain development and physical change, making proper nutrition essential to their physical, cognitive and emotional well-being.

The first 1,000 days are a time of remarkable change when the brain, body and immune system develop at a pace unmatched by any other stage of life:

The same possibility of this significant 1,000-day period also makes it a phase of immense risk, especially for families without access to sufficient food. According to the World Food Program, 45 percent of deaths in children under 5 are caused by malnutrition.

Inadequate nourishment during pregnancy, infancy and toddlerhood can cause profound and often irreversible damage to children’s physical and mental growth, permanently impairing their bodily health, ability to learn and likelihood of having strong economic prospects in the future.

As defined by the World Health Organization, malnutrition is a condition caused by deficiencies, excesses or imbalances of calories or nutrients in an individual’s diet. Malnutrition can occur when people are unable to access the quantity or quality of food they require to survive, grow and lead a healthy life. Global efforts are focused on combating malnutrition by optimizing nutrition early in life to ensure long-term health benefits.

Severe cases of malnutrition, such as acute malnutrition, result from a significant deficiency of essential nutrients. They lead to critical health issues such as wasting and stunted growth, weakened immune function and increased susceptibility to infections and diseases.

Poor dietary diversity, irregular eating patterns, lack of a balanced diet or frequent consumption of poor-quality foods also contribute to nutritional deficiencies and can manifest in vastly different ways, from extreme hunger to obesity. Undernutrition occurs when the body doesn’t get enough calories, protein or micronutrients to maintain healthy tissue and organ function. It often leads to weight loss and muscle wasting. Micronutrient deficiencies, also known as “hidden hunger,” occur when essential vitamins and minerals, such as vitamin A, iodine, iron and zinc, are insufficient in the diet, deficiencies that can lead to severe health problems.

Malnutrition is especially damaging to children. A deficiency of vital nutrients in a child’s diet can cause conditions such as stunting or wasting, which refer to low height for age and low weight for height, both of which are linked to impaired physical and cognitive development.

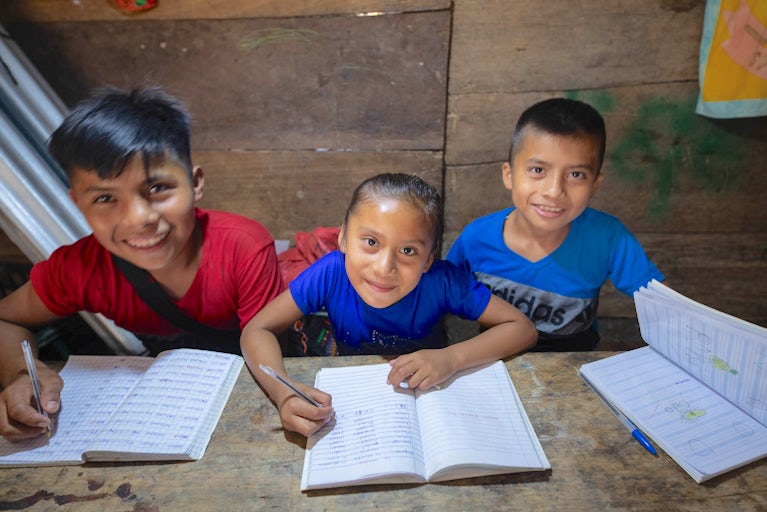

Poor nutrition can cause irreversible damage to a child’s growing brain, affecting their ability to perform well in school and earn a good living. Malnutrition can also lead to chronic health conditions and permanently affect a child’s quality of life. In extreme cases, it can cause muscle shrinkage, blurred vision, breathing difficulties, irregular heartbeat and organ damage.

Globally, 45 million children under 5 suffer from wasting and around 149 million are affected by stunting. Every year, undernutrition claims the lives of more than 3 million children before they turn 5.

Malnourished children are more likely to grow up to become adults with compromised physical and mental health, limited educational and earning ability and, therefore, a higher risk of being unable to afford a nutritious diet for their own children, which creates a vicious cycle of poverty and malnutrition that can each fuel the other for generations.

Diet-related noncommunicable diseases, such as heart disease, stroke and cancer, can be traced back to early malnutrition. This is why the United Nations, in partnership with local organizations, governments and NGOs, has emphasized the importance of addressing hunger, malnutrition and food insecurity in the Sustainable Development Goals.

While malnutrition is caused by densely rooted issues, including food insecurity, inadequate health care, and poor hygiene and sanitation, poverty remains the primary determinant. Malnutrition-related deaths among children under the age of 5 predominantly occur in low- and middle-income countries, where poverty amplifies the risk of malnutrition. The impact of how well or poorly mothers can care for themselves and their children, based on the economic and social resources available to them, dramatically shapes a child’s development.

Families living in poverty often cannot afford quality food and health care for themselves and their children. For smallholder farmers who rely on growing crops to earn income, poverty can also make it impossible to participate fully in the food system and generate sustainable profits from their farms.

In many rural areas, limited awareness of maternal and newborn care — especially the importance of dietary diversity — deepens the effects of poverty on early childhood nutrition. Cultural norms, such as breastfeeding taboos or women being expected to eat last, can also prevent children from getting the nutrients they need.

Proper nutrition during pregnancy is essential to support fetal development and set the stage for lifelong health. When women have consistent access to nutritious food, accurate information and supportive health services, both mothers and children are more likely to thrive.

Still, around the world, many women face misinformation, cultural pressure, and a lack of access to nutrition services, education and the resources needed to feed their families well.

Because children in their first 1,000 days rely entirely on their mothers for nourishment, maternal well-being becomes a critical link in the chain. Supporting women with knowledge about breastfeeding, dietary diversity and family nutrition — along with access to prenatal care — is one of the most powerful ways to improve child health during this vital window.

Heifer International is working with mothers and families around the world to put nutritious food on their plates, overcome generational poverty and malnutrition and pass on the wealth of good health to their children.

In Senegal, for example, one mother, Nafi Sane, learned during a community weighing day that her young daughter was malnourished. With guidance from Heifer-trained coaches through the Nutrition Enhancement Project (KAYRA), she prepared fortified porridge using locally available ingredients. Her daughter recovered, and today Nafi shares this knowledge with other mothers in her village as a community facilitator, leading trainings on nutrition and dietary diversity.

Heifer is helping 25,000 families, including Nafi’s, address malnutrition by improving their livelihoods and earnings and educating mothers on exclusive breastfeeding, complementary feeding after 6 months, and how to monitor their children’s growth. We’re also working with the local government to expand families’ access to health centers for consultation and treatment of child malnutrition.

“I noticed a big change in the child. Today I can say that my daughter has recovered from malnutrition. … She is doing well, and I am very happy. … That is why I keep on giving [the porridge] to my daughter. In addition to that, I realized that it is very nourishing for pregnant and breastfeeding women too.”

Globally, Heifer is partnering with more than 1.3 million smallholder farmers to build dignified livelihoods and strengthen food systems, which can provide nutritious food, education, health care and other essentials for themselves and their children for the long term.

We also help farmers establish kitchen gardens where they can grow diverse produce at their homes and provide resources so farmers can improve the productivity of their animals and provide nutrient-dense animal-sourced foods, like milk and eggs, for their families’ consumption.

This work is enhanced in many cases by nutrition training, which helps people understand the nutritional value of the foods available in their communities and make informed choices about what to purchase, raise or plant.

The sessions also tackle cultural norms that contribute to hunger and malnutrition, such as unequal food distribution among family members, to ensure a safe, healthy and nurturing environment for mothers and their children — for the first 1,000 days and beyond.

Malnutrition during the first 1,000 days of life can have devastating and long-lasting effects on a child’s health, development and future potential. By understanding the different types of malnutrition, their consequences and implementing effective strategies for prevention and intervention, we can make significant strides in combating this global issue.

Cart is empty

Success!

Please be patient while we send you to a confirmation page.

We are unable to process your request. Please try again, or view common solutions on our help page. You can also contact our Donor Services team at 855.9HUNGER (855.948.6437).

Covering the transaction fee helps offset processing and administrative fees that we incur through taking payments online. Covering the transaction fee for each payment helps offset processing and administrative fees that we incur through taking payments online. Covering the transaction fee for each payment helps offset processing and administrative fees that we incur through taking payments online.