Russell Hartzler, a Michigan farmer and donor to what was then called The Heifer Project, received a letter from Germany in October 1949. A cow the Hartzler family donated had weathered an ocean journey and was in its new home, and the new owners wanted to offer thanks.

Dear Mr. Hartzler,

First I want to give my hearty thanks for the joy you gave us with your gift. I would like to introduce myself briefly. I’m a refugee from Yugoslavia, and my background is from the farm. We had at home a farm with 40 hectares of very good soil, which we had through fi ve generations as our own. Then came the war, and the terrible time after the war... What it means to leave house, farm and animals to which you felt so very close, is hard to say...

I brought one horse along from my old home in Yugoslavia and so I started on a very small farm again with just 2 hectares of very sandy bad soil. I sowed and worked a lot on the soil but the harvest was very small, so that I had to work besides the farm work in a furniture factory...

My dear Mr. Hartzler, it surely takes lots of love to give a cow away, but you hardly know and I can’t express what a great joy you gave to my whole family. It’s hard to say what it means, after 5 years, to have a cow in the barn again...

There came many packages from the U.S., and always my daughter asked: “Daddy, don’t we have any relatives there, so that they could send us a package also?” I just could comfort her with the words: “Don’t worry. God will carry us through the need.”

And now look — an unknown human being gave us through God’s blessing not a little package, no, he gave us a life to help us out of the deep need. It isn’t only the material value alone; it meant so much more to us. We received more courage for living.

With many hearty greetings,

Your family,Jakob Renner

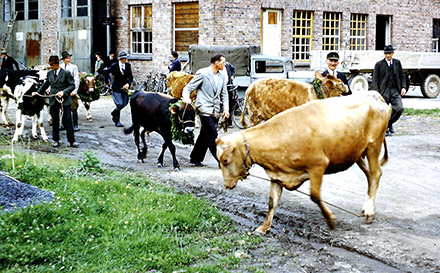

Renner’s letter is just one of many sent by grateful families struggling to regain their livelihoods after the war. Heifer Project representatives worked closely with German government offi ces to deliver gifts of more than 4,000 heifers and bulls from 1949 to 1961.

Traveling through Germany today, one would have little clue as to the hardships faced by this leading economic power following World War II. The war, however, left many of the country’s cities in rubble with food in short supply, as it was all over Europe. In Germany, this shortage was compounded by the fact that the country had to absorb some 12 million people of German heritage expelled from Eastern European countries, like the Upper Silesians who came to North Rhine-Westfalia.

For more than a decade, refugees poured into Germany with little more than the clothes on their backs. The government created settlement areas in forests damaged by the war, moors that were drained, abandoned military bases. The poor soil of these areas heightened the despair of settlers who had been forced to abandon prosperous farms. It was to the plight of these farmers that the Heifer Project responded.

Heifer was one of many organizations approved by the German government to lend assistance. Recipients signed an agreement form pledging to pass on the fi rst female off spring of their heifer to another family in need. Heifer representatives made follow-up visits to recipients and encouraged them to write thank you letters to their donors, resulting in some long-term friendships.

It seems fair to say that Heifer International played a significant role in helping Germany get on her feet again after the war and, along with programs like the Marshall Plan, in helping build the good will that has existed between our two nations for decades.

Some of Heifer’s contributions toward rebuilding went on display last year as part of “For Body and Soul,” a 14-month exhibit in Ratingen, Germany. The museum is the Oberschlesisches Landesmuseum (Upper Silesian State Museum), off the beaten tourist path in the northwestern German state of North Rhine-Westaflia. Gathered therein is the history of the Upper Silesian people, a people from miles away with a strong tie to this industrial region. Today, the area of Upper Silesia overlays a small piece of northern Czech Republic and a larger piece of southern Poland.

When King Frederick the Great took control of Silesia for Prussia in the 1700s, he invited coal miners from North Rhine- Westaflia to come and help develop the rich mineral resources of Silesia. So when Silesians of German heritage were forced from their homes following World War II, it was to North Rhine-Westaflia that many of them fled, and where many of them were able to rebuild their livelihoods with Heifer’s help.

In recent decades, many of the Upper Silesians began to pool together documents and artifacts of their history, and many of those pieces were included in the Upper Silesian State Museum exhibit. Walking through the museum, one discovers a people with strong family ties and a culture and creativity all their own: a people from a land where iron ore is crafted into filigree jewelry and coal is carved into jet black works of art; where the honeycomb frame for beehives was invented, as was the process for making sugar out of beets; where the cultivation, preservation and preparation of food has been and continues to be a central part of the culture.

As curators pieced together the exhibit, they reached out to get more information about Heifer’s contribution to rebuilding Upper Silesia. “One of the topics will be strategies of providing nourishment in times of shortage and crisis throughout the history,” museum educator Eliska Hegenscheidt- Nozdrovicka explained. “In this context, we would like to introduce the issue of the seagoing cowboys and the Heifer Project in Silesia and Poland in 1945-1947.”

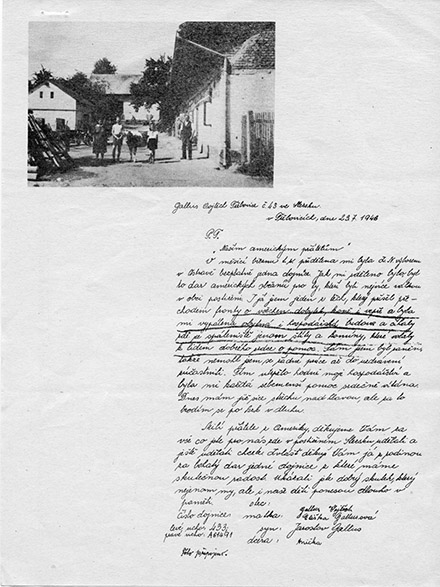

This thank-you letter included in the display reflects the significance of these Heifer project gifts.

July 23, 1946

To our American friends,

In March, a cow was assigned to me free of charge by the Provincial National Committee in Ostrava. I was told this was a gift from American citizens for those in the village who were affected most by the war. I am one of those who lost all their cows, horses, and pigs during the German retreat from the war; all that remains of my burned house are bricks and chimneys calling goodhearted people for help. I myself was wounded and unable to do my share in rebuilding. My farming suffered, and the smallest help was most welcome. Today I have a roof over my head, but I am deep in debt.

Dear friends from America, we thank you for all you have done and still want to do for us in our war-torn Silesia. Especially, my family and I thank you for the rich gift of my only heifer, which brings us great joy. You have done a good deed that not only we, but also our children, will long hold in our memory.

From the Wojcich Gallus family of Trebovicem, Silesia

“When we received the information from Ms. Miller we were quite fascinated with the unique concept of this hunger relief project. Donating livestock and thus helping people help themselves as well as the adventurous logistics of transportation were some of the factors why we chose it as an example of a postwar private hunger relief initiative in Silesia,” Hegenscheidt-Nozdrovicka said.

The devastation of World War II had significantly diminished the ability of the Upper Silesian and Polish people to feed themselves. Into that void stepped UNRRA with shipments of draft horses and cattle, as well as staple relief items. Seven of those shipments included Heifer Project animals. The exhibit highlighted these shipments to Czechoslovakia and Poland and the seagoing cowboys who delivered them.

“The rich selection of photographs and documents from Ms. Miller’s and Heifer International’s archive collections enabled us not only to show the transport procedure of the donated heifers and horses to Poland and Czechoslovakia. They stand for much more. These photographs witness ruined postwar Europe with bombed cities and hungry children; and they show optimism, faith, and goodwill of men and women in far-away America helping people they had never met,” Hegenscheidt- Nozdrovicka said. “We wanted to relay an attitude of hope and new beginnings to prompt reflection on our times of plenty in comparison to the hardships in the past.”

By Peggy Reiff Miller, Heifer International historian